Challenges Faced By Small But Critical Allied Health Professions

Most people have heard of a physiotherapist, occupational therapist, dietitian and a podiatrist – but do you know what a pedorthist, orthoptist, prosthetist or music therapist does? The allied health workforce includes a number of very small, very niche, but very important professions. We call these “small but critical workforces”.

Small may be beautiful, but sometimes small size creates risks to the sustainability of a profession.

What is a small but critical workforce?

New South Wales Ministry of Health defines small but critical workforces as ‘Workforces which contribute critical and essential elements of a comprehensive health service, and are currently experiencing threats to meet systems needs now and into the future’. Workforces or professions that are considered to be “small but critical” will change over time, and also according to different jurisdictional needs.

How do allied health professions form?

Most allied health professions developed during the 20th century in response to specific population needs. For example, sonographers, developmental educators, audiologists, exercise physiologists, genetic counselors, operating department practitioners, pedorthists and perfusionists all professionalised towards the end of the 20th century in response to a new need or new technology.

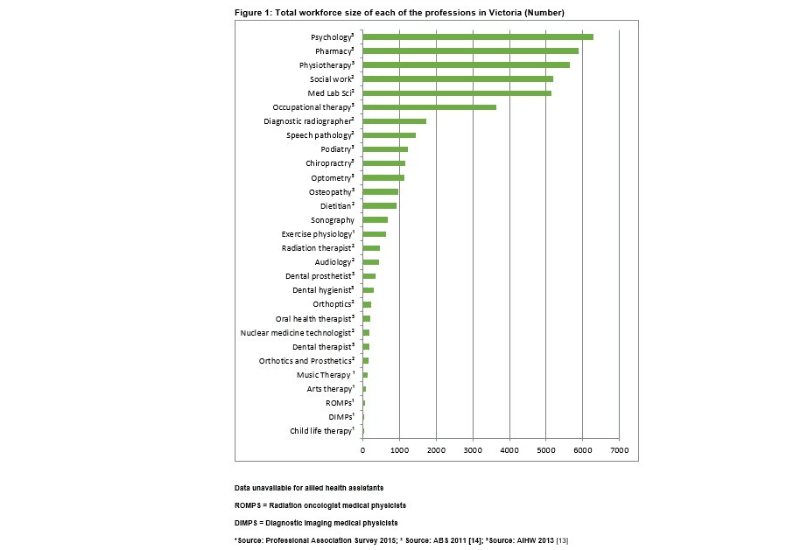

In some countries, like Australia, the health regulation system allows new professions to form in response to new needs or new technologies. Some professions will remain relatively small due to their niche focus, for example see the figure below that shows the relative sizes of professions from an environmental scan of allied health professions in Victoria, Australia. However others will transition through a growth phase. The small size of some professions creates some risks for their professional growth and sustainability.

The development of a new profession depends on several pre-requisites. The workers first need to organise themselves into a single professional association. Then they need a critical mass of workers who agree to abide by a common set of standards or protocols which are determined by the professional association.

Those standards are developed and delivered through a formal education structure (normally a university). They are maintained and monitored by the relevant professional body. In most countries, allied health professions require at least a Bachelor Degree level of qualification which is delivered by a university or other higher education provider.

Professional closure and occupational monopoly

For a profession to be successful, they need to convince society of their value, and to achieve “professional closure”. Professional closure is the way the profession creates a monopoly over their area of practice. This, in turn, creates opportunities that are unique to their own members – normally by limiting access to funding to recognised (registered) members of the profession.

Sometimes, professional closure is achieved through state regulation, such as the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) in the UK or the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency in Australia (AHPRA) and state regulatory bodies in Canada and the United States.

State regulation generally protects the professional title and may stop others from undertaking components of that role. But, for instance, in Australia, the majority of allied health professions are self-regulating. In other words, they do not have state protection of their title or role, but their professional association has created a monopoly market for their workforce on behalf of their members. More information about jurisdictional differences in health regulation is available in this article.

For example, in Australia, speech pathologists, dietitians, sport and exercise scientists (to mention only a few) are not regulated by AHPRA. Instead, their professional body establishes and endorses the standards of practice.

Only members of the profession who are registered with the professional body have access to specific funding, such as Department of Veterans’ Affairs, National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), Medicare. This is a very effective form of professional closure because it limits the ability of other workers to compete the same area because they can’t easily access funding to do the same work.

The wicked problem facing small but critical workforces

Herein lies the “wicked problem” of the support and growth of small but critical occupational groups. Increasingly tight university budgets mean that courses with small student numbers are not commercially viable to run.

Self-regulation means that new occupational groups can grow to meet market needs relatively quickly, and in a high quality way, with little direct government investment to develop the new profession. However, professions requires government support to help fund training in universities.

The challenge for small professions is that they require time to become established as an allied health profession to achieve recognition in the workplace.

Much like any start-up, a lead-in period is required for any new university course to ensure its establishment, gain traction and reputation in the market, and build student numbers and demand.

The current higher education funding environment does not encourage risk-taking. Recent university funding challenges mean that universities may not be able to deliver small programs that do not pay their way.

The case for pedorthists

One example of a small but critical workforce in Australia is the pedorthic profession.

Pedorthists play an important role in the prevention and management of diabetes related foot disease; the provision of adaptive footwear for people with congenital disabilities or foot trauma; and adapting footwear to reduce the risk of falling.

Over the past decade, pedorthics has evolved from a technically based, vocational qualification to a recognised allied health profession supported by the introduction of a Bachelor of Pedorthics (BPed) delivered by Southern Cross University in Australia. The BPed is the only degree level training for pedorthists offered in the southern hemisphere.

The scientific rigour of a university-based training program ensures the standards and consistency of the treatments required to meet the needs of the high-risk populations pedorthists serve. It also provides the workforce with the technical underpinning, language and skills to engage with the health workforce as allied health professionals, rather than technicians, which is an important component of driving high quality outcomes for patients.

However, as a small course, there are questions about the sustainability of university delivery of the BPed. As the only degree level qualification for pedorthists this will immediately limit the growth of the profession at a time of rapidly increasing need for specialised foot care experts, nationally and globally,

The pedorthic profession is small, and declining, with only 35 Certified Pedorthist Custom Makers, or 0.14 Pedorthist Custom Makers per 100,000 population in Australia. In comparison, the Netherlands and Canada have 18 and 1.3 certified pedorthists per 100,000 people respectively. As a proportion of the number of people diagnosed with diabetes, this represents 2.5 pedorthists per 100,000 in Australia versus 9.0 and 389.6 in Canada and the Netherlands respectively.

Diabetes accounts for less than half of the pedorthist’s workload, yet, based on the epidemiology and risks associated with diabetes alone, Australia has insufficient pedorthists to meet population needs.

Aditionally, the pedorthic profession in Australia is undergoing a workforce transition with the older members of the profession reaching retirement over the next 5 – 10 years, but insufficient, degree trained pedorthists to meet current demand.

A number of other small but critical workforces in allied health have only one recognised university training program because of their small size. The ability to access to ongoing training is an important consideration for both the introduction and the sustainability of small workforces.

Without the credibility of an undergraduate degree, small professions face challenges recruiting new members to the profession, may risk losing their status as an allied health profession, and are less able to build a scientific basis for their work. This will have a direct impact on the accessibility and quality of those professions for the community.

Other challenges for small but critical workforces

For small professions, the costs of maintaining and managing self-regulation can be prohibitive. One proposed solution is the introduction of international regulatory standards that can be adopted by small workforces globally.

However there are a range of other challenges for small but critical allied health workforces, including:

- lack of knowledge and awareness of the profession, which in turn leads to fewer referrals for the service and a smaller pipeline of prospective workers

- lack of visibility at policy and service levels

- smaller groups of workers tend to be under-represented in large organisations, therefore they lack a voice within institutional structures and

- under-representation in leadership roles

- very small professions may not be captured in national census data, which further diminishes the visibility of the professional group

Conclusion

Self-regulation creates a way for allied health professionals to rapidly and fairly efficiently respond to new and emerging population needs by developing new roles. However small workforces face several challenges that impact on their sustainability, including lack of access to university training, and the high costs of maintaining self-regulation and professional accreditation. It is unlikely that free market forces alone can support these small professions, and some level of state intervention is required to ensure the sustainability of small but critical workforces.

—

AHP Workforce provides allied health workforce planning, strategy and consulting for employers, managers and stakeholders. Click here to view our consulting portfolio. For tailored, data-driven allied health workforce solutions, contact us today.