12 Strategies To Address Allied Health Workforce Shortages

Updated: 7th February, 2023

Australia is facing critical allied health workforce shortages across several disciplines. Workforce shortages are a burning platform for the allied health professions, but there is no central data, planning or coordination of the workforce to look at solutions collectively.

For several reasons, there are few statistics available on the actual extent of allied health workforce shortages in Australia. In fact, we even lack accurate workforce supply data for most self-registered allied health professions.

The Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report recognises the value of allied health in the delivery of person-centred care and increasing the efficiencies and effectiveness of primary health care. One recommendation of the Taskforce is to increase the commissioning of allied health services by Primary Health Networks in under-serviced areas to supplement care provided by general practice teams—this will require both an increase in the allied health workforce and a redistribution to the areas of greatest need.

Other recent federal policy drivers that have increased allied health workforce demand include the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety and the roll-out of the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Both aged care and disability currently report serious allied health workforce shortages.

This article draws on our previous allied health workforce research, as well as approaches that have been used during other periods of rapid, substantial allied health workforce shortages. We propose 12 solutions that can be used to help meet the demand for the allied health workforce.

1. Train more allied health professionals

Interestingly, allied health training programs have been increasing over the past decade. For example there are now more than 20 higher education institutions offering occupational therapy and speech pathology programs in Australia. The AHPRA website lists 51 approved programs of study for physiotherapy in Australia, 58 for occupational therapy and 28 podiatry programs (although a handful of podiatry courses are non-qualifying programs, such as podiatric surgery or prescribing).

Most allied heath programs in Australia are now at least four year undergraduate training, although several two-year graduate entry Masters programs are available. Some institutions also offer three-year Doctoral training. In other words, the lead time to increase allied health workforce capacity through training is at least two years—assuming new courses increase their recruitment immediately.

The capacity of higher education providers to increase allied health workforce training in Australia is currently constrained by two bottlenecks: 1. the lack of appropriately qualified academic allied health practitioners; and 2. insufficient clinical placements for students. Together, these factors limit the ability of higher education providers to increase allied health training programs and places in Australia in the short to medium term.

It is interesting that despite the growth in allied health training the number of allied health vacancies continues to increase in many professions. Without accurate workforce planning data, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of the continued shortages, but the growth of the NDIS and changes to aged care funding are commonly cited causes of the redistribution of the allied health workforce.

2. Introduce new models of training

Traditional models of training for most allied health professions involve university based training with outsourced clinical placements. However, new models of training which are 80% clinically based and only 20% university based, or degree apprenticeships which are currently being introduced in universities in England to train health workers such as this physiotherapy degree apprenticeship, instantly increase the supply of workers. This also creates opportunities for hierarchies in the workplace (enabling delegation) that are currently only available if allied health assistants are employed.

Students need to have a relevant job to be able to apply for a degree apprenticeship. This model would require some rapid restructuring of the allied health workforce and training approaches to enable it to take place in Australia; currently degree apprenticeships are not available for allied health training in Australia.

Other flexible training approaches that have been used (which precede degree apprenticeships) include incremental training models, such as step-on-step-off programs. This approach moves away from the time-based achievement of qualifications to the incremental achievement of specific competencies. For example, some universities in Australia now offer a Diploma in Allied Health Assistance (promoted as a career as an allied health assistant) and an Associate Degree of Allied Health (promoted as a pathway to various allied health careers).

Flexible training models like step-on-step-off programs allow the incremental credentialing of practitioners by providing several exit points during professional training. This means that workers have a marketable skill, more quickly, which can be responsive to the context in which they work. These types of programs have been attempted by a number of institutions in Australia and the UK. One barrier to their uptake is that employers have not responded with appropriate roles for ‘partially’ qualified allied health professionals, with the exception of allied health assistants (AHAs) (who only require vocational training at present).

Incremental training can also be facilitated using micro-credentialing. Micro-credentialing involves a short training time to learn a particular task to meet a specific, focused (and often, high volume) need. For example RMIT has introduced a micro-credential in Digital Health, and The University of Sydney has a range of micro-credentials to aid professional development of qualified clinicians. For clearly definable tasks, such as aged care assessment services, micro-credentialing might be a way to rapidly address allied health workforce shortages.

We discuss these ideas in more detail in this paper.

3. Upskill junior practitioners / new graduates quickly

Despite a great deal of focus on and investment in graduate employability, many employers still complain that new allied health graduates are not work-ready when they graduate. This has been a particular challenge levelled at two-year graduate entry masters programs, but it also applies to some four-year, undergraduate training programs. COVID-19 presented particular challenges for graduates due to restrictions on clinical placements for many training programs.

Similarly, some employers have suggested that poorly-prepared graduate allied health practitioners are less valuable than experienced allied health assistants.

For students currently enrolled in training programs, this could and should be addressed by the higher education providers through appropriate workplace integrated learning approaches. However, supported induction and orientation to the workplace—particularly in areas of high demand—could help alleviate some of the challenges of workplace readiness of new graduates. There are several examples of these approaches in rural and regional areas, such as the pilot of the Rural Generalist Training Program introduced by Queensland Health.

New graduate support frameworks could include appropriate mentoring, supervision and support in the sectors where they are most needed, such as in aged care and disability. Support should take place in the context of an appropriate delegation framework to ensure that new graduates are doing appropriate work for their level of qualification, and not work that should be delegated to others, such as AHAs.

High quality allied health onboarding programs are one way to rapidly upskill workers to increase their productivity.

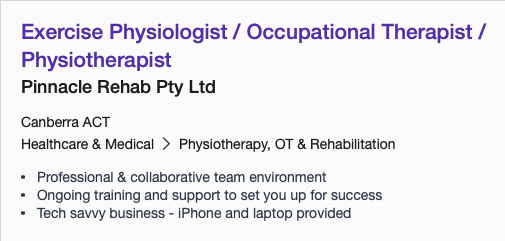

4. Substitute shortage professions with others

As this position advertised on Seek.com.au illustrates, workforce substitution is already taking place. Several organisations are advertising for exercise physiologists OR physiotherapists OR occupational therapists. Workforce substitution is fairly common during periods of workforce shortage. Other documented areas of workforce substitution include nurses for podiatrists and in the mental health sector.

Allied health professionals are particularly adept at transferring roles between different professional groups, and there are largely no regulatory restrictions to prevent this, except for some restricted tasks.

Substitution can be an effective way of filling workforce shortages when there is a relative oversupply of one profession compared with another. The current advertisement-to-allied health staffing ratios suggests that few allied health professions are sitting idle at present.

Substitution is different to delegation because it involves giving a task away to another worker who is not under your division of labour (see this article for a detailed explanation of the differences between substitution and delgation). One challenge of workforce substitution (and delegation) is that once roles are given away, it can be difficult to get them back again.

5. Import more overseas-qualified allied health professionals

Australia has had a long tradition of relying on overseas trained practitioners to meet our own health workforce needs.

COVID-19 has presented an obvious, practical challenge to importing health practitioners. However there are several other structural issues related to the allied health workforce in Australia that are likely to make workforce migration increasingly challenging.

- The UK has recently substantially reduced its own allied health training programs so is likely to be experiencing their own allied health workforce shortages.

- There are ethical challenges of relying on foreign-trained workers to meet workforce demands, particularly if they are employed from low-to-middle income countries (such as India and South Africa).

- Australian allied health practitioner salaries are low compared with the United States, approximately on par with the NHS, but according to NUMBEO the cost of living on almost all indices is around 20% higher in Australia than in the UK. Housing prices in Australia are some of the highest in the world according to this article, although the OECD data tells a slightly different and more confusing story. Bottom line: aside from our fabulous lifestyle and excellent COVID-19 track record, our cost of living is likely to make Australia a less attractive contender for several overseas-trained practitioners.

- The burden of locating and importing foreign workers largely sits with employers. It is an expensive and time consuming process.

- The lack of accurate allied health workforce data means that many perceived shortage professions are not on the skilled occupation list.

6. Create new roles

Allied health professions are particularly nimble at meeting market niches and creating new workers. A good example is the developmental educator which is a relatively new allied health profession that has evolved specifically to meet the needs of people with disability. Developmental educators are formally only recognised as an AHP in South Australia and they are a small profession which has great potential for growth in the current market.

It takes time to create new professions, however there is evidence in the aged care and disability assessment sectors of the development of a targeted aged care assessor role which is completely vocationally trained. It is during times of workforce shortage that this kind of role can quickly step in to meet market needs as we have seen in other sectors.

For example podiatric surgeons were granted professional (registered) status in Australia and the United Kingdom in response to workforce shortages of orthopaedic surgeons and demonstrated expertise in the understanding of foot pathology. Strictly speaking, podiatric surgeons are a specialised branch of podiatry, however their journey to professionalisation as surgeons shows how existing professions can create new roles by taking on roles that are typically performed by others (in this case, orthopaedic surgeons).

During times of workforce shortages or workforce shocks—as we are experiencing now—the opportunities to up-skill and expand roles to fill other gaps are greater than ever. For example pharmacy prescribing is finally being introduced as a way to reduce pressure on general practice which patients are largely supportive of.

7. Ditch the ‘dirty work’ – or delegate lower risk, less skilled tasks

The term ‘ditching the dirty work’ was first coined by a sociologist, Hugman, in 1991 and has become a well-known phrase to describe the way that professions offload tasks that do not require their expertise to a less qualified workforce, enabling the profession to upskill and professionalise.

Allied health professionals have responded to this in different ways. There is a lot of good evidence for the effectiveness of allied health assistants internationally (for example see our Chapter on The support workforce within the allied health division of labour) or our article on optimising the use of allied health assistants.

There are no regulatory reasons why allied health assistants (AHAs) cannot be employed, but despite the fact that there has been good evidence of their effectiveness for nearly two decades, health services in Australia have been very slow to embrace them.

AHAs provide a rapid and fairly efficient way to scale up the capacity of the allied health workforce. The challenges of introducing AHAs (or equivalent) are the funding models, particularly in a fee-for-service environment. There is still some ambiguity about the ability of allied health professionals to seek reimbursement for services delivered in part by AHAs.

Delegation normally takes place between a higher skilled or more highly qualified worker, and involves some kind of clinical supervision between the delegator and the delegate. Delegation does not always involve allied health assistants or support workers and can take place in an interdisciplinary team context and across professional boundaries.

8. Increase the workforce participation rate of qualified AHPs

Overall, the allied health professions are predominantly female, with over twice as many females as males in the registered professions. There are large profession-based variations in gender distribution, for example speech pathologists are well over 90% female. Further, the allied health cohort is young—dominated by the 20-34 year age group.

Data on the workforce participation rate for allied health is sketchy (given that we don’t even have accurate numbers on the AHPs themselves), but it is reasonable to assume that people of child-bearing age and / or their partners may be working part-time.

A 2022 NDS workforce census reportedthat the number of hours worked by allied health professionals was declining rapidly and is on average 18.2 hours per week.

One way to reduce allied health workforce shortages is to increase the participation rate by providing high quality, affordable child care for allied health professionals who care for young children. Alternatively, parents of young children might be able to increase their participation through the provision of more flexible locum or casual opportunities that may complement their lifestyle needs.

Accurate data on the allied health workforce participation rates are critical to help guide accurate workforce planning and training pipelines.

9. Reduce allied health workforce attrition (increase retention)

As with all other areas of allied health workforce planning, there is little understanding of the attrition rates of allied health professions in Australia. Theoretically, this data could be extracted from relevant data for the NRAS registered professions, but we could not find any recent published analysis of workforce attrition for allied health professions in Australia.

Published registration data provides a crude analysis of practitioner intention to stay in their respective professions, but there is no analysis of actual attrition figures.

Much of the focus on workforce attrition has taken place in particular sectors and areas of disadvantage, particularly rural and remote practitioners.

Professional bodies need to have an understanding of their workforce inflows and outflows and, alongside employers, develop strategies to keep practitioners in the workplace as long as possible.

Our article on Allied Health Retention discusses some evidence-based strategies to optimise allied health workforce retention.

Further work is required to define what is meant by attrition, understand the causes, measure it, then introduce strategies to reduce attrition. We propose that standard workforce metrics are adopted across the allied health workforce to provide some workforce planning benchmarks.

10. Attract qualified practitioners back to the professions

During COVID-19, several countries introduced strategies to re-engage workers who had left the workforce, resulting in a rapid increase in workforce capacity. The health regulatory and accrediting systems are probably better prepared to re-engage the returning workforce than ever before.

Strategies to attract returners to professions can include:

- Bringing clinicians back from non-clinical roles. Data available from registered professions in Australia suggests that a high proportion of many registered allied health professionals are engaged in non-clinical roles.

- Reviewing recency of practice rules for those whose registration has lapsed and providing programs to facilitate rapid, safe reskilling of those workers.

- Bringing staff back from retirement.

- Actively targeting people who have left the profession to go to other sectors to return to clinical practice.

For organisations, our Allied Health Employee Lifecycle article on Attracting Allied Health Professionals discusses strategies to become an employer of choice and increase opportunities to attract workers to your organisation.

11. Change allied health funding models

We outline the median pay levels for a range of Australian allied health health professionals in this article on allied health workforce shortages. There are a number of challenges with the current funding models for allied health. Episodic reimbursement rates by heath insurers and the Medicare Benefits Scheme are poor. Assessment and care coordination time is largely unrewarded but can be heavily bureaucratic and time consuming. Poor reimbursement for allied health has created market failure in regional and rural areas reducing their access to necessary allied health services.

A further challenge for allied health payment is the incredible complexity of the funding models. For example, the figure below shows the different sources of funding used by occupational therapists in Victoria. Not all providers would access funding from every funding source, however many occupational therapists would work with multiple funding bodies. The workload costs of managing and administering funding from multiple different providers is rarely accounted for.

Job advertisement data suggests that there is some pressure on salaries in rural and remote areas.

The physiotherapy position below, based in Darwin, illustrates the premium paid to regional allied health practitioners (the average physiotherapy salary is $69,205AUD according to Payscale.com).

The advertisement below (from Seek.com.au in March 2021) illustrates the acute pressure on the social work workforce, with this position advertised for a final year social work student in regional New South Wales.

Like most front-line workers, including teachers, nurses and personal care workers, allied health professionals’ salaries remain relatively low, career progression can be difficult, and salaries have not increased for some time (based on available data).

Interestingly, despite the relatively low median pay for the allied health professions, there seems to be little difficulty attracting students into most allied health profession training programs, however low pay is likely to be a driver of attrition. While there is little, large scale empirical data to underpin this, poor reimbursement was a common theme and area of dissatisfaction for allied health professionals surveyed in the Victorian Allied Health Workforce Research Program (e.g., see physiotherapy report).

The funding models will need to change in tandem with other structural changes to the workforce, such as the introduction of a well structured, and properly reimbursed delegation framework that lets degree-qualified practitioners employ and delegate to allied health assistants…and to charge for it. This would increase AHP capacity, income and increase the potential for career development opportunities, which are also a source of contention for AHPs.

12. Introduce new, more efficient models of care

Many allied health services in Australia are delivered on a one-to-one basis and often rely on episodic, fee-for-service funding models. Individual, fee-for-service care models create a far less flexible workforce than team-based funding approaches because of the disincentives to lose business to other providers. This is one reason the NHS (which is a large, single monopoly employer of allied health providers) has had so much success in role / task transfer, delegation and the introduction of new, subordinate roles in comparison with Australia.

Queensland Health has been a leader and innovator in the introduction of new models of care for allied health. More information is available on their website and we evaluated the program in this paper.

There are opportunities to increase efficiencies in the following ways:

- Deliver (and appropriately fund) group-based AHP therapy interventions, as opposed to individual interventions.

- Develop and deliver online training and education packages that do not require direct, 1:1 intervention with clients (such as telehealth falls prevention models).

- Introduce delegated models of care (e.g., allied health assistants).

- Create ‘hub-and-spoke’ models of specialisation, where a ‘generalist’ allied health practitioner can engage the services of a more specialised practitioner to meet needs of smaller sections of communities (this approach is used to support regional / rural practitioners).

- Use telehealth to support hub-and-spoke models.

Conclusion

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to increasing allied health workforce supply, and the reality is that a combination of all of the initiatives mentioned above will be required. There is currently no national statutory body with responsibility for overseeing and planning the allied health workforce. One of the biggest challenges to implementing the interventions above is the lack of available data on the allied health workforce—from the both supply and demand sides.

Allied heath workforce planning, if it is done at all, is managed by the various state and professional jurisdictions. The interconnectedness of the responses above—including the need for a coordinated response with national training providers—shows that allied health workforce planning cannot be effectively managed in a siloed way.

In our paper Why Is It So Difficult To Understand and Plan The Allied Health Workforce In Australia we discuss the challenges of accurately collecting and collating allied health workforce data, and suggest some solutions.

The allied health workforce attracts some of our best and brightest talent. This is an opportunity to rethink the workforce to reallocate AHP skills to the areas where they can make the greatest difference, and create a more nimble, (and sustainable) better differentiated workforce to meet the needs of the population.

AHP Workforce has a range of insights and solutions for allied health workforce planning, which you can browse here. | View our Projects Portfolio.

AHP Workforce provides allied health workforce planning, strategy and consulting for employers, managers and public sector stakeholders. For allied health workforce solutions, contact us today.

With regard to Point 2 “New models of training” there is a further option – move from the common 1 to 1 student to practitioner model of student placements in allied health. This involves introducing innovative practicum models that are educationally sound, founded on quality partnerships with industry that not only better meet the needs of the clients/participants/patients, the practice educators and students but enable more students to learn through participating in the workplace. These models can be co-designed, trialled and embedded within 12 -18 months and potentially would allow universities to enrol more students relatively rapidly. See references below for examples. If industry partners can be found who are willing to innovate and contemplate the idea that students can be a benefit not a burden (and i am not talking about unpaid workers!), there are many other mutually beneficial opportunities that would create more placement opportunities and enable universities to enrol more students.

Foley, K., Attrill, S., & Brebner, C. (2021). Co-designing a methodology for workforce development during the personalisation of allied health service funding for people with disability in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06711-x

Nisbet, G., McAllister, S., Morris, C., & Jennings, M. (2020). Moving beyond solutionism: Re-imagining placements through an activity systems lens. Medical Education, 55, 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14345

Nisbet, G., Thompson, T., McAllister, S., Brady, B., Christie, L., Jennings, M., Kenny, B., & Penman, M. (2022). From burden to benefit: a multi-site study of the impact of allied health work-based learning placements on patient care quality. Advances in Health Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10185-9